World’s Columbian Exposition

Construction begins at the World’s Fair site, 1892.

The Woman’s Building, designed by Sophia Hayden, under construction.

Image from the Surface Atlas showing some of the Foreign Building locations at the World’s Columbian Exhibition. The Brazil Building is seen at the left. From Burnham et al. 1989:n.p.

Map of the World’s Columbian Exposition fairgrounds, from Rand McNally and Co. 1893.

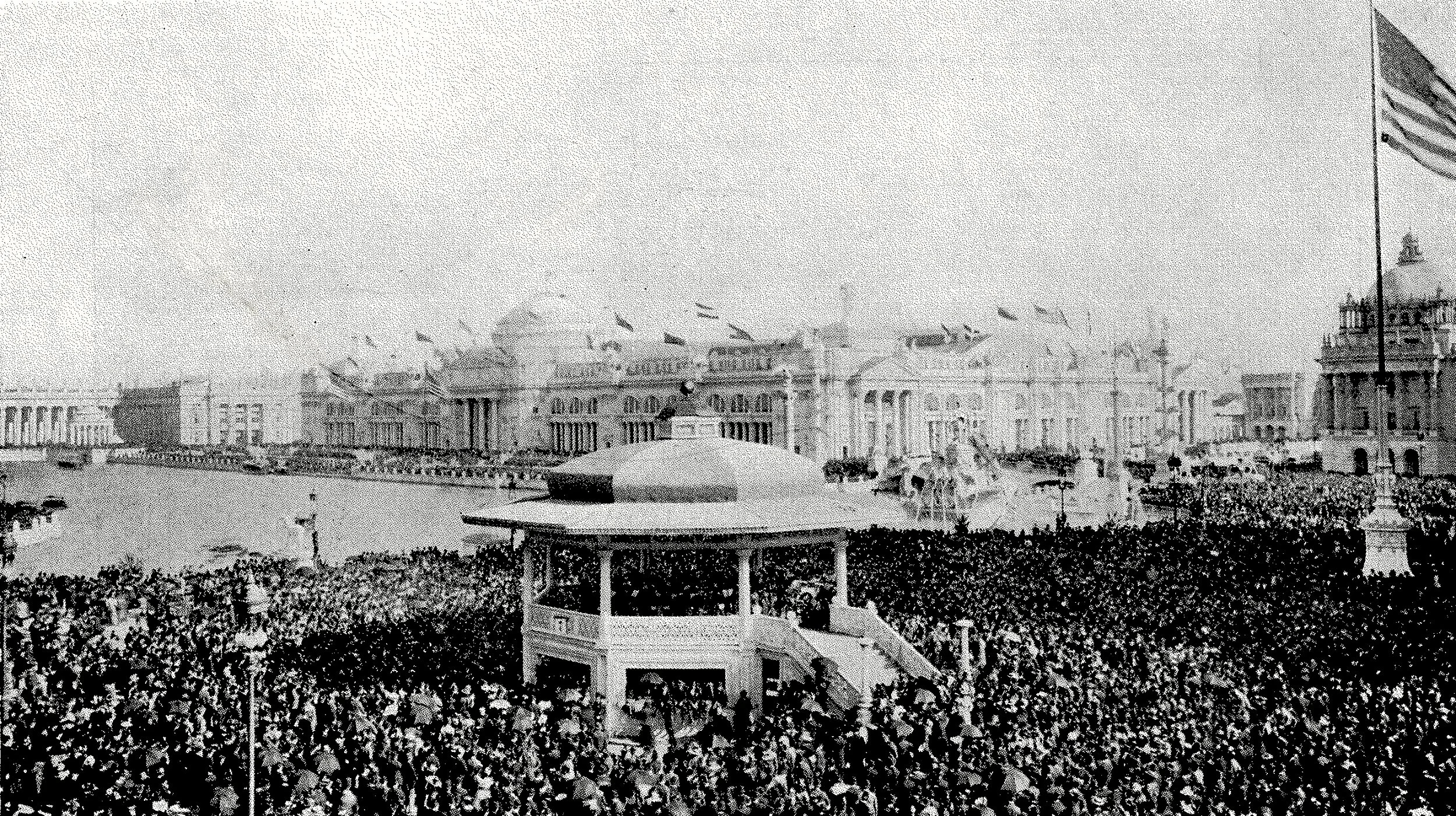

Crowds at the Fair on Chicago Day, October 9, 1893.

The non-white performers who worked and lived within the Midway Plaisance exhibits, including “Little Egypt” (center) who entranced tourists with her danse du ventre, were often portrayed in demeaning and racist fashion.

Contextualizing the Fair

Chicago’s Jackson Park was “the center of the world” between May and October 1893 when millions of sightseers from many countries visited and revisited the area to experience the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. The Chicago Fair presented an encyclopedic display of raw materials, manufactured goods, new inventions, fine arts, entertainments, foods, and ancient and modern architecture. The Fair’s Midway Plaisance contained “living zoos” of people from Dahomey, Java, Egypt, Turkey, and more, along with the Irish Village, Libbey Glass exhibit, California Ostrich Farm, and sights like the world’s first Ferris Wheel and the Captive Balloon ride. All of this was held in a temporary “city” that was designed to be demolished at the Fair’s end.

But what are world’s fairs, and why is the Chicago Fair so important?

“The 1893 Chicago fair, including its exhibits, entertainments, and ephemeral architecture, must be considered within the larger tradition of international world’s fairs and expositions. Between 1865 and 1925, 360 million people attended world’s fairs in Europe, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand, a figure compiled from the attendance data of the major international fairs (Findling and Pelle 2008:413–417)” (Graff 2020:22). “At a time when the total U.S. population was approximately 63 million, over 27 million tickets were sold to the event,” equating to between 12 and 16 million individual visitors (Graff 2020:5-6).

“Nineteenth century world’s fairs as cultural forms emerged from the social currents of industrial capitalism, where a customer base of millions might be reached to consume the goods and ideas on display, each event characterized as a veritable ‘clearing-house of civilization’ (Palmer 1893:5)” (adapted from Graff 2020:5-6).

Architects and Architecture

“Daniel H. Burnham, director of works for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition”… “[was] charged with hiring and creating a board of architects to design the main buildings of the fair, selected ten prominent American firms, deliberately choosing five from Chicago and five from elsewhere to promote a national, rather than solely Chicagoan, sense of the enterprise: Richard M. Hunt (New York), George B. Post (New York), McKim, Mead and White (New York), Peabody and Stearns (Boston), Van Brunt and Howe (Kansas City, Missouri), Burling and Whitehouse (Chicago), Jenney and Mundie (Chicago), Henry Ives Cobb (Chicago), Solon Spencer Beman (Chicago), and Adler and Sullivan (Chicago) (Higinbotham 1898:29). While working on plans for the 1893 Chicago fair, many of these architects accepted private commissions in the up-and-coming Astor Street District of the Gold Coast. There they designed extravagant homes for the very men who, again, not coincidentally, swelled the ranks of the World’s Columbian Exposition’s governance committees…[N]otable for their work in both Jackson Park and in the Gold Coast is the firm of Adler and Sullivan, who designed the Transportation Building for the fair during the same time period as they designed the Charnley House” (Graff 2020:11).

“Located seven miles south of Chicago’s Loop, the site in Jackson Park hosted an American fair even larger than the massive 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition” (Graff 2020:5). “In comparison to the 72 acres that made up the 1889 Paris fair”, and the 285 acres of the Philadelphia exposition, “the total size of the Jackson Park fairgrounds was 686 acres and was populated by over two hundred structures (de Wit 1993:49). To prepare the site for building, construction laborers transformed the natural landscape of Jackson Park, dredging lagoons, carving an island from a peninsula, and planting trees throughout the site. With the exception of Louis Sullivan’s Transportation Building, the main structures of the White City were unified examples of Beaux-Arts design—even a common cornice height of sixty feet had been set by committee to maintain this visual unity. Set up in a biaxial arrangement, the Court of Honor consisted of these main buildings and a series of lagoons, with the rest of the site dotted with smaller structures that did not have to adhere to strict stylistic guidelines. State and foreign government buildings, some built to evoke the distinct architecture of their region, were situated near the northernmost boundary of Jackson Park. The Midway Plaisance, a strip of land west of the main grounds, so-called as it was located ‘midway’ between Jackson and Washington Parks, housed commercial concessions and was not formally arranged with neoclassical architectural conventions. (Graff 2020:29-31).

Ephemerality and Ideology

The 1893 Fair ended on October 30, 1893, after the assassination of popular Chicago mayor Carter Henry Harrison, Sr., and without the planned closing ceremonies. The site was to be turned over to the South Parks Commission to be transformed back into usable parkland.

Although world’s fairs like the 1893 Chicago Exposition were intentionally designed to be impermanent, the ideological messages they generated lasted long after the final buildings were dismantled or destroyed. There are far too many ideas and goods that stemmed from the 1893 Fair to mention, but a few important ones might suffice. The Midway Plaisance in particular provided a rubber stamp for a racist vision of non-white Americans as barbaric and less human than whites, paving the way for legislating further inequities and forwarding American imperialist dreams (Rydell 1978: 255). The City Beautiful Movement, with its legacy of neoclassical municipal buildings, shaped cityscapes in all parts of the US (Wilson 1989). And today, whenever you take a bite of a Vienna Beef hot dog, enjoy the snap of Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit gum, or visit the Field Museum, you are also consuming the echoes of the 1893 Fair.

< Previous Page | Next Page >