Simon Pokagon and The Red Man’s Rebuke/the red man’s greeting

Portrait of Simon Pokagon.

Simon Pokagon, far right, at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition’s Chicago Day, where he delivered his book and spoke before a crowd of 7,000. This photograph was provided with the written permission of Dr. John N. Low, who holds its copyright (2007, 2015).

An article from the Chicago Inter Ocean, January 23, 1899:5.

Simon Pokagon and Chicagoland Potawatomis

Leopold Pokagon (1775?—1841) was a Potawatomi chief who was head of a village in the St. Joseph River Valley in southwest Michigan (Low 2016:28). He attended the 1833 Treaty of Chicago negotiations, serving as one of the seventy-seven Potawatomi signatories to the Treaty, which granted the U.S. all of the land west of Lake Michigan to Lake Winnebago (in Wisconsin). Leopold had negotiated an amendment to the Treaty that allowed his band to stay in the area instead of being removed west to Kansas on the Potawatomi Trail of Death (Low 2016:29).

After Leopold’s death, Simon Pokagon (c. 1830—1899) became a leader of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, if not the “Hereditary and Last Chief” of some accounts (Low 2016:40). He was active as “an author, and an advocate for American Indians” who was “always welcomed by the ‘progressives’ in Chicago’s ‘Gold Coast’” (Low 2016:40,42); these likely included neighbors of the Charnleys and other occupants of the Charnley-Persky House.

Chicago Day at the Fair

Over the six months of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, the Fair organizers set aside many days as so-called “special days,” recognizing different groups of people, places, fraternal organizations, and occupations. There were more requests for special days than there were days of the Fair, so many had to be held together. These special days included Norway Day (May 17), Guatemala Day (July 3), Stenographers Day (July 22), California Pioneer Day (August 5), Ottoman Empire Day (August 31), and many, many more (Rossiter 1897:406-463). But none of them had the popularity or attendance of Chicago Day.

Chicago Day took place on October 9, a date was chosen to honor the anniversary of the 1871 Chicago Fire and to play into the narrative of Chicago’s phoenix-like return from ashes. An estimated three-quarters of a million people visited the Fair that day (Rossiter 1897:453), the single busiest and most crowded day of its six-month run.

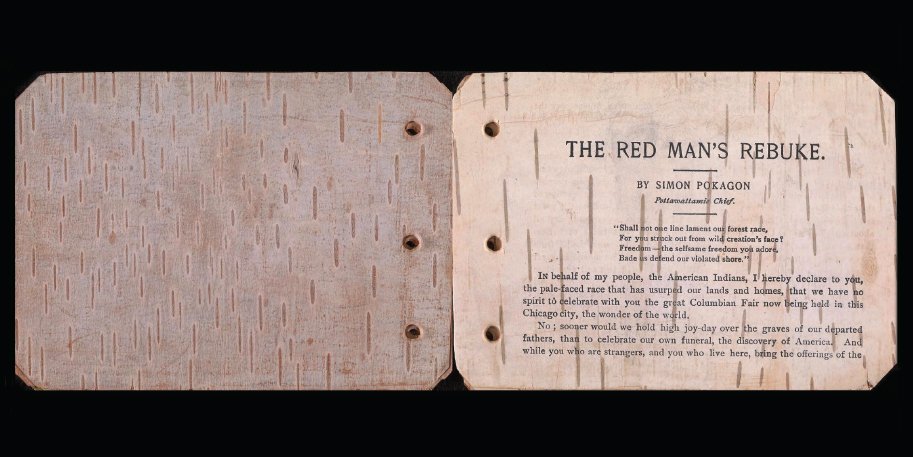

The Red Man’s Rebuke/The Red Man’s Greeting

On that very well-attended Chicago Day, Simon Pokagon presented a facsimile of the deed to Chicago, wrapped in birchbark, to Chicago’s mayor, Carter Henry Harrison (Low 2016:59). He also shared and sold his book, The Red Man’s Rebuke (alternatively titled The Red Man’s Greeting) at the Fair on the Midway Plaisance (Low 2016:46). Printed on birch bark, this book was Pokagon’s challenge to the dominant racial ideology of the Fair—which held white Europeans as the pinnacle of humanity—using his own lived experience as the descendant of chief Leopold Pokagon and a Potawatomi member dealing with white settlers and their descendants.

He began his text with a powerful proclamation:

In behalf of my people, the American Indians, I hereby declare to you, the pale-face race that has usurped our lands and homes, that we have no spirit to celebrate with you the great Columbian Fair now being held in this Chicago city, the wonder of the world. No; sooner would we hold high joy-day over the graves of our departed fathers, than to celebrate our own funeral, the discovery of America. And while you who are strangers, and you who live here, bring the offerings of the handiwork of your own lands, and your hearts in admiration rejoice over the beauty and grandeur of this young republic, and you say, “Behold the wonders wrought by our children in this foreign land,” do not forget that this success has been at the sacrifice of our homes and a once happy race (Pokagon 1893:5).

You can read the entire text of The Red Man’s Rebuke here.

Pokagon after the Fair

In the years after the Fair, Simon Pokagon continued his advocacy for Native Americans. He wrote several other books (e.g., O-gi-maw-kwe Mit-i-gwa-ki, Queen of the Woods, 1899) and continued to give public speeches. He delivered these words during a speech to a white fraternal order, the confusingly named Improved Order of Red Men, in 1898:

Historians have recorded of us that we are vindictive and cruel, because we fought like tigers when our homes were invaded and we were being pushed toward the setting sun. When white men pillaged and burned our villages and slaughtered our families, they called it honorable warfare; but when we retaliated, they called it butchery and murder. . . . But let Pokagon ask, in all that is sacred and dear to mankind, why should the red man be measured by one standard and the white man by another? (Pokagon 1898 in Low 2016:55).

Near the end of his life, parts of his novel, Queen of the Woods, were performed at two schools in Chicago’s Hyde Park, the neighborhood of the 1893 Fair, which shows his continuing influence in the region. Simon Pokagon died of pneumonia on January 28, 1899; his legacy continues today.

< Previous Page | Next Page >