Racialization of Domestic Laborers

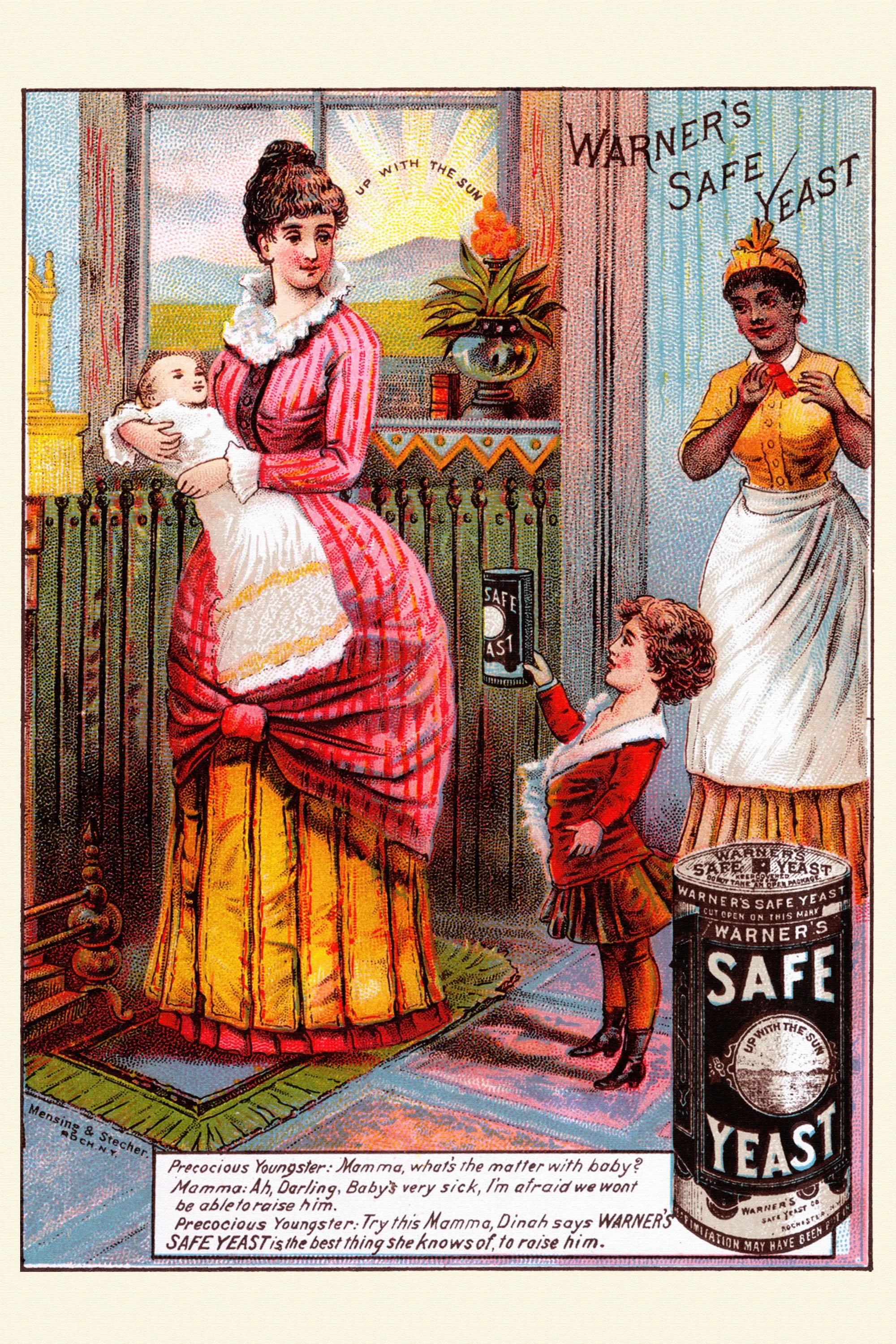

Warner’s Safe Yeast ad featuring a domestic woman of color.

A table of Census data on residents of the Charnley House, including live-in domestic laborers, 1900-1940.

Black women learning dressmaking.

This page from the 1920 Census lists the residents of the Mecca who used the 3348 S. State St. address. Many of the women list domestic service jobs as their occupation. 1920; Census Place: Chicago Ward 2, Cook (Chicago), Illinois; Roll: T625_306; Page: 8A; Enumeration District: 84.

The female servants who worked in the Charnley-Persky House and the women of the Mecca Flats, many of whom found employment in domestic positions throughout Chicago and its elite suburbs, reflect a distinctly unequal pattern in the racial, ethnic, and national origins of those whom Chicago-area elites preferred to hire.

The 1870 US Census was the first to systematically record women’s employment; it showed that approximately half of all employed women in the United States were in domestic service (Cowan 1983:120; Graff 2020:114). By 1920, 46% of all Black women employed in the U.S. worked as domestic laborers or in laundries, as compared to 22% of foreign-born white women (Palmer 1990:xiii).

There is an even more dramatic split among women employed in the domestic service sector in Chicago during the period examined by this exhibit: so many Black women, including residents of the Mecca Flats, working as domestics, yet so few of them were among the many domestics working in the Gold Coast neighborhood of the Charnley-Persky House.

Who Worked in the Charnley-Persky House?

The documentary record regarding the women and men who lived and worked in the Charnley-Persky House is unfortunately scarce. However, the US Census provides their names, ages, and places of birth along with their racial identities and other glimpses into their lives.

As the table on the left side of the page indicates, the successive owners of the Charnley-Persky House consistently employed people to play crucial roles in the maintenance and functioning of their household—roles that the owners would have been reluctant to play (or to be known by others to have played) given their self-conscious status in the American class and racial hierarchy of the time. Those noted in the Census as live-in servants would have occupied the small bedrooms on the third floor of the house, accessible via a separate staircase hidden from the public and family areas of the house (U.S. Census 1900; Barton 1987:10). However, like other elite Chicagoans, including later owners of the house, “the Charnleys may have employed additional servants such as a butler, cook, laundress, handyman, or coachman when their needs required it” who lived elsewhere in the city (Cromley 2004:122).

The table at left also reveals some important patterns within the Charnley House itself and its peer residences on the Gold Coast. “First, the national origin of the Astor Street servants changes across time, although until 1940 the majority of the servants employed in each household were white Northern Europeans, then replaced by white Americans. Second, their ages vary from nineteen to seventy, and only in 1940 were the domestic workers themselves part of their own legal domestic relationship: marriage. These data points do map to the overall trends in the United States during the first decades of the twentieth century, where single, white, immigrant women who lived in as servants gave way to married women (white and black) who worked as day labor in domestic spaces (Cowan 1983:121–22)” (Graff 2020:115).

Without exception, the domestic laborers employed in the Charnley House and recorded in the Census from 1900 to 1940 were white. This pattern matches that seen in the majority of residences in the Gold Coast. Indeed, a look at the neighborhood’s pages from those same Census years also reflects a steady number of white servants:

1900 (14 domestic laborers across 7 households): 6 from Sweden (and one born in Illinois with Swedish parents); 3 from Ireland, 1 from Denmark, and 1 from Italy. 12 of the 14 were women; all people listed on this page are white.

1910 (24 domestic laborers across 9 households): 8 from Sweden, 4 from Germany, 4 from the US, 2 from England, 2 from Scotland, and 1 each from Canada, Ireland, Italy, and the Netherlands. 18 of the 24 were women; all people listed on this page are white.

1920 (14 domestic laborers across 8 households): 3 from Sweden, 3 from Germany, 3 from the US, 2 from Finland, 2 from Ireland, and one from Canada. 13 of the 14 servants were women. For the first time, there are 3 Black and 1 “Mulatto” residents listed consisting of two married couples, all born in the U.S. In each of these couples, the male member works as a domestic servant and the female member is not listed as being employed. 12 of 14 servants were women.

1930 (22 domestic laborers across 9 households): 8 from Sweden, 6 from the U.S., 2 from Ireland, 2 from Norway, and one each from England, Germany, the Netherlands, and Scotland. One of the households included a Black couple (listed as “Negro” in the Census) who worked as servants—Kemp and Birdie Black. 20 of 22 servants were women.

1940 (15 domestic laborers across 10 households): 6 from the US, 4 from Sweden, 2 from Germany, and one each from Ireland, Norway, and Scotland. One household has a domestic laborer categorized as “Negro,” Helen Johnson, originally from Louisiana. 12 of 15 servants were women.

Overall, the preference for employing domestic laborers in the neighborhood of the Charnley House was for single white women, often from western or northern Europe. Only in the 1930s and 1940s were any domestic laborers non-white, and in both cases, they were still in the minority. As we shall see, this hiring pattern does not reflect the fact that a large population of Black Chicagoans were working in domestic laborer occupations in other parts of the city.

What occupations did the women of Mecca Flats Have?

Taking a look at even one page from one government census gives a lot of insight into the occupations of the Mecca Flats tenants, including a large number of women who were in a domestic laborer occupation. The page shown at the left lists the tenants of 19 different flats at the 3348 South State Street address, a total of 50 residents. Of the 29 women mentioned, 14 report occupations: 3 maids (at a furniture store, for Pullman Lines, at a hotel); 3 laundresses (two for private families and one at home); 1 dressmaker (at home); 1 seamstress (at home); 1 mantle maker (in a gas lamp factory); 1 usher (at a theatre); 2 waitresses (in restaurants); 1 dishwasher (in a café); and 1 nurse in general practice (1920 Census). These working women were categorized as mulatto (25), Black (3), or white (1) and ranged in age from 18 to 68, with a median age of 34.

The majority of these positions, even from one page of 50 Mecca Flats tenants, shows an over-representation of blue-collar domestic service, whether in a private residence or business. This is in contrast to the 21 male tenants of that census page from the Mecca, who were employed as barbers, billiard hall managers, boot blacks, butchers, cooks, chauffeurs, cigar store owners, laborers (in a foundry, a mattress factory, a steel mill, and a packing company), porters, and waiters.

Nancy Green, who lived in Bronzeville not far from the Mecca, was employed in domestic service when she wasn’t working as “Aunt Jemima.” Yet she, like many of the women in the neighborhood of the Mecca Flats, worked outside the Gold Coast in other wealthy, white households. While further research is needed to determine their shape and extent, the persistence of these patterns is quite evident, and gives us yet another insight into the racial and class hierarchies of Chicago across time.

< Previous Page | Next Page >